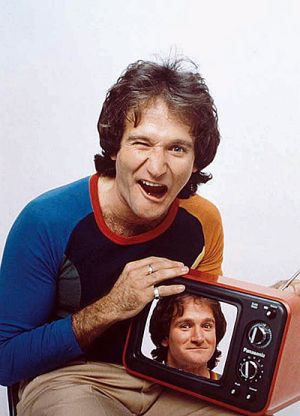

When extraordinary talents work together, results can be truly spectacular. This is the story of Robin Williams and Michael Dressler, who took the Time magazine cover photo that the National Portrait Gallery installed to memorialize Williams following his death on August 11. The original Time cover from March 12, 1979, bore this bold cover headline: “Chaos in Television…and What It Takes to Be No. 1.”

Former colleagues called Williams a human vente structure gonflable dynamo, a genius—the guy in Juilliard’s scholarship program who left in his junior year after being told there was nothing more they could teach him.

Dressler is an accomplished photographer of people—from presidents to humorists, scientists to athletes, celebrities to the Ku Klux Klan. Driving him is the passion for taking photographs that would be important 10 years from the day he shot them.

In any competition, success is sweetest when the stakes are high—like making it to the cover of Time, the nation’s top news magazine in 1979. Time’s West Coast photo editor demanded “impeccable perfection,” and it was Dressler’s job to get it.

Two Talents, Like Minds

At the launch of his TV career and before the Time cover shoot, Williams held an audition for a photographer. Dressler got the nod, after an hour or two. In an interview with him, Dressler told me, “[Williams and I] hit it off. We were very much of the same mind. We had the same humor. We even looked like brothers.”

Often, Williams invited Dressler to visit him and his wife at their Malibu beach house. Dressler would ask, “With or without camera?” It was always the photographer’s call. When Williams encouraged him to body surf, Dressler would decline, preferring to walk on the beach and snap a picture of the actor in action.

The two played off each other’s humor and strengths: Williams, with his boundless spirit, and Dressler, with his quest for taking photos that were honest, which meant nothing staged or contrived.

Dressler explained to me, “I usually don’t do multiple shots at a single time. I get it, or I don’t.”

He felt responsible to capture the moment for the many people who weren’t there.

Plans for the Time shoot unfolded quickly. Dressler got the go-ahead around 8 p.m. Williams met him at the studio at 10 p.m., following a rehearsal. Assistants and observers converged, including Williams’ agent and Dressler’s brother, who had worked with him in advance on the setup and strategy. Dressler, who aims for spontaneity, had to get his best, honest shot in a film studio where everything is controlled.

Williams was playful that evening, and as usual, the two helped each other. Dressler suggested ideas, Williams gave them a try, and the ideas evolved. A lively Robin Williams was photographed holding a brightly colored card, until someone suggested replacing it with a small TV. The drama intensified; it was late in the evening when assistants rushed out to locate an open appliance store. They finished the shoot at midnight, ran the film to Hollywood, then to LAX, where a private plane was waiting. Once in New York, the Time staff inserted the image of a mellow Williams onto the blank screen.

Was it the impeccable perfection Time wanted? The mystery loomed until the very last minute. Dressler received the “yes” call after the cover was in print.

“When I told him, Robin was so excited,” Dressler recalled. “He was off the charts, so touched that the two of us did it together.”

A few days later, it felt like everyone in Malibu had that cover in hand.

Takeaways for Business and Leadership

Dressler’s Robin Williams story helps me understand the challenges of a creative business. Once again, I realize that when you reach out to creative people, you become more sensitive to the creative mindset and how to bring it into your life and work.

• “Make It Honest” was Dressler’s mantra, passion and style. He focused to seize the moment and make it real. In business, honesty affects everything: the quality of decisions, relationships, outcomes, success in the marketplace, credibility and trust. More than ever, honesty is a business imperative as 24/7 news, social media and engagement expose problems and poor results faster than ever.

To keep it honest, executives need to create an uninhibited exchange of ideas. It takes candid, open relationships to get unfiltered facts, unburdened by spin and politicking. It requires you to be honest with yourself and to expect that colleagues will do the same. Only with the best information and dialogue can you stretch and make that “iconic shot.”

• Be Flexible. But there are no guarantees that a challenge will match your strengths. Business managers need to be flexible, which can be difficult for tough-minded executives. Many are locked into an approach or a career track, even as it becomes obsolete. Becoming a dinosaur can happen overnight. You need to stay current and adapt to change. I encourage my colleagues to talk with people from different fields to spark creativity and spot new possibilities and threats.

• Create the Shared Thrill of Pursuit. The Williams/Dressler relationship demonstrates what happens when talented people share common views and values. It is easiest to do your best work when you collaborate with people who think the same way about the factors affecting success and innovation. The alignment of minds fuels the thrill of pursuit, a focus to create something incredible and an openness to figure out how.

• Recognize Accomplishments. Unlike many business people, Williams was comfortable giving feedback and recognizing great work. Dresser remembers the actor’s spontaneous reactions. Williams was so proud of what they did together, and he made it known. Following the cover shoot, he told Dressler, “I think you have the cover of Time magazine.” Robin Williams was joyful, at peace.

Posted on the Wharton Magazine blog, October 9, 2014